It’s been a busy start to the year for renewable energy and net zero.

The year began with a thought-provoking article in The Economist on the topic of offshore renewable energy and the role it may play in Europe’s future economy.

The article was really positive and gives a lot of reasons to be hopeful. In short the article was about the benefits that cheaper, more renewable, energy would bring. There was talk of data centers moving to Norway to take advantage of cheap, clean energy, allowing large organisations to meet their environmental commitments.

More recently, there was a review made by Chris Skidmore into the UK’s net zero strategy, which raised calls for the UK to further raise its ambitions. This was reiterated by the CBI at the time. CBI Economics were also commissioned by the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) to write a report on the growth of the UK’s net zero sector. We were delighted to contribute data to answer that question.

The UK is making progress with Net Zero, but is it enough?

Recently we refreshed our Energy Storage RTIC (with many thanks to Harini) and we found almost twice as many companies. Energy storage is a key component of providing cheap and renewable energy for everyone and through our platform I’ll show how the sector is developing.

The UK has an ambitious plan for offshore renewable energy.

The UK has an ambition to have 50GW of offshore energy by 2030. To put that in perspective, that’s about 20% more than peak demand. The UK is fortunate (OK, maybe a stretch) to have windy weather. It is a valuable resource though and we have been making good progress towards our target – as recently as January of this year we generated 21GW of energy from wind.

The chart below shows the currently finished offshore wind projects, alongside the upcoming projects (view definitions here). The light blue shaded area shows the UK’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), demonstrating the abundance of wind energy that we have the ability to capture.

I want to avoid drawing up a leaderboard – we can always have more renewable energy; we can always be greener. Many other countries have made significant progress in decarbonising their electricity grids too. Germany has around 60GW of wind energy capacity already. Denmark has a higher share of wind energy as a proportion of their overall energy generation.

So, the UK’s current achievements should be recognised, but it doesn’t make the UK unique. This is more and more true, as the US begins a large-scale drive for net zero. But, as highlighted by the CBI Economics report and the Chris Skidmore review, it’s not just a drive for net zero, it’s also a drive for competitiveness in the future economy.

Net zero can directly shape our economy, through the creation of new jobs and industries. It can also indirectly shape our economy, as was highlighted in the economist article. Renewable energy is now a cheaper form of energy production than gas, and even nuclear. Reducing the cost of electricity will allow our business base to compete on an international level.

Reflecting on this opportunity, Chris Skidmore has highlighted that there’s more that we need to do to remain competitive. He states that UK businesses are missing out on opportunities because of the UK’s investment environment.

Thankfully there is worldwide recognition of the importance of renewable energy and the opportunity it presents for growth. However, this has seen increased competition in creating economies that will serve our future. As mentioned above, the US has announced a large subsidy program to attract investment into renewable energy, which the EU is responding to. There are some concerns that the UK may fall between the gaps.

Why is energy still expensive, despite a significant proportion now being generated with cheaper methods?

The UK has been investing in wind energy for a considerable period of time. Since 2009, the UK’s offshore wind energy capacity has increased by a factor of 20.

Wind energy is now cheaper per unit of electricity than building gas powered power plants. This is a major milestone. However, why aren’t we seeing the benefit of this? Why is the UK not more competitive on energy prices? Wind energy should make the UK grid less sensitive to external price shocks, right?

Yes it should. However, the UK’s grid operates a pricing mechanism where the price of a unit of energy is equal to the cost of the most expensive method of producing electricity on the grid at that time.

Why is that done? Wind energy is great, and as we’ve all most likely experienced, the wind is usually fairly reliable in the UK. However, there is still variability and, in times of demand, other forms of energy production need to fill the gap between demand and supply. For example, in January’s cold weather we were relying heavily on gas to meet our energy needs and coal plants are being prepared for use, should the need arise.

To allow energy producers that use more expensive resources like gas or coal to fill the demand without making a loss, the price has to be set at the cost of production for themselves. That’s why the UK’s energy price has still increased drastically over the past year or so.

Full use of the UK’s offshore energy capacity requires infrastructure improvements

Variability in renewable energy poses other challenges too. Say wind production is too high for demand, wind turbines must be turned off, to prevent the national grid from being overloaded. In this case, potential energy is wasted.

The national grid relies on being able to transfer energy around the country as needed. Unfortunately, if too much energy production is occurring in one area of the UK, this can cause strain on the grid. In these circumstances suppliers may be paid constraint payments, to lower their output and reduce the strain on the grid.

At the moment the UK’s approach is to monitor the cost of constraint payments and compare this to the cost of investing in additional infrastructure.

While I understand the challenge of upgrading infrastructure in an affordable way, and that delaying investment will allow better technology to be used, it is almost inevitable this additional infrastructure will be needed – especially if electric cars are going to increase in use.

Yes, payments to renewable energy suppliers will allow suppliers to continue investing and building their capacity, but if this capacity can’t be used because of network constraints, there is a question of what benefit is there to be gained.

Offering payments to constrain capacity is a deadweight loss and there is a question of whether the money for constraint payments could be better used in investing in energy storage, or increased connections to other countries, which would allow us to export any excess energy.

There are a couple of solutions here. The interconnectors between the UK and other surrounding nations are a really good idea. When the cost of UK energy is lower than our surrounding neighbours – when there is an excess of wind energy – we can export our excess energy. Likewise, when wind energy production is low, we can import energy from our neighbours.

The role of Energy Storage

I mentioned before that the UK set an internal record for wind generation. On the 10th January, wind generation contributed 21GW of energy to our grid. In the second half of January, with the colder weather, wind energy production has been around 5GW. If we were able to store more of this energy, we would be less dependent on gas and coal and the average cost of producing electricity would be lower. How can we store energy for use during calmer periods?

There are various ways of storing the excess energy, from storage in batteries, to hydroelectric power and hydrogen. As highlighted in the Economist article, hydrogen storage is an exciting avenue of development.

Hydrogen storage

The UK has ambitions to have 5GW of green hydrogen production capacity by 2030. This amounts to around 10% of our peak daily demand. The 5GW ambition is only the beginning, as the UK has a cross-cutting hydrogen strategy, ranging from hydrogen applications in trains and planes, and in the long term, there’s a plan to replace natural gas, which we use for heating homes, and household appliances, with hydrogen.

The UK is well situated to store hydrogen. Firstly, because of its unique geography. Hydrogen can be stored in salt caverns and currently this is done in 4 places around the world. One of these places is off the coast of Newcastle!

Secondly, because of the companies that are operating in the UK. The UK has seen a rapid increase in the number of hydrogen storage companies – we recently refreshed our mapping of the hydrogen storage sector and we found over 5 times as many companies!

The UK’s hydrogen storage sector

Here’s what you should know about the hydrogen storage sector in the UK. Firstly, it’s well distributed across the UK. Mouse over the chart below to find out the number of companies in each local authority.

You can see clusters in the north, around Hambleton, Lancaster and Edinburgh. Many companies are registered in London – this isn’t unusual. As well as companies that legitimately operate in London, some companies headquarter in London, but operate elsewhere.

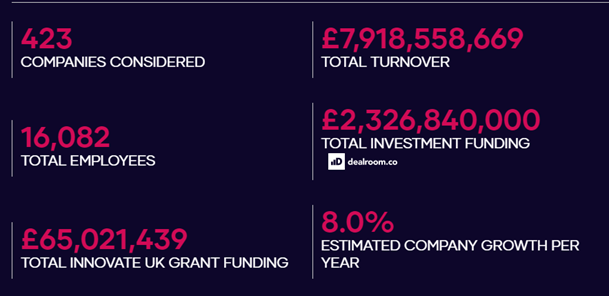

This is an extract from our platform, allowing us to quickly see there’s over 400 companies working on hydrogen-based energy storage in the UK, with a collective turnover of almost £8bn.

Our platform can analyse over 5 million companies, of which we have classified over 200,000 emerging economy businesses using website text and machine learning. Our intuitive tool allows users to make their own lists, compare data sets and much more.

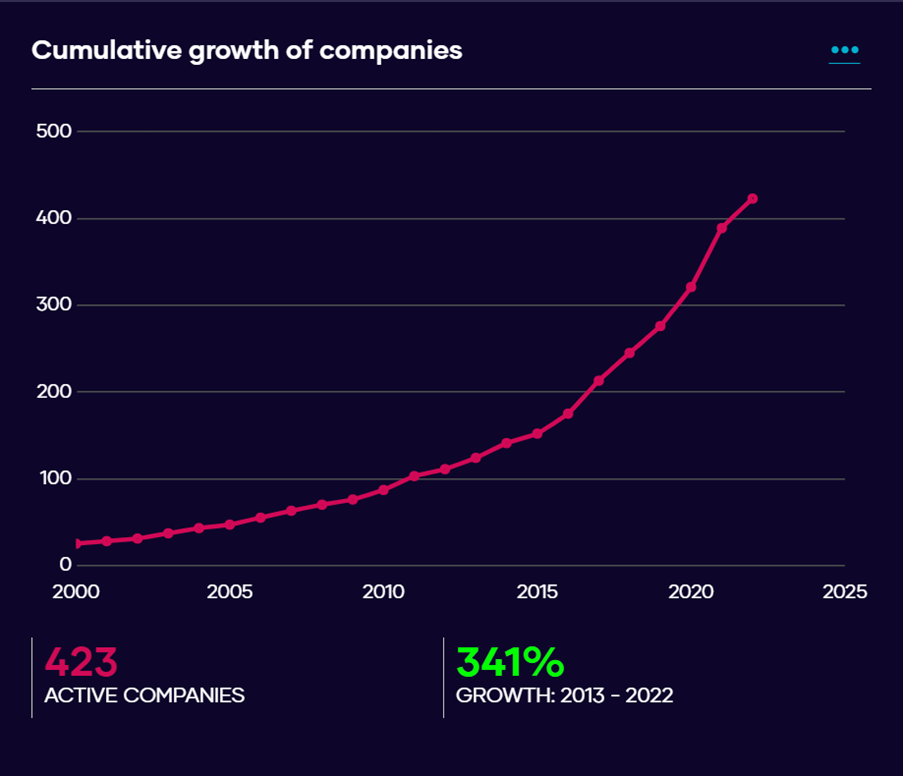

The current growth rate of 8% is indicative of a broader trend. The number of companies operating in hydrogen storage has tripled since 2013.

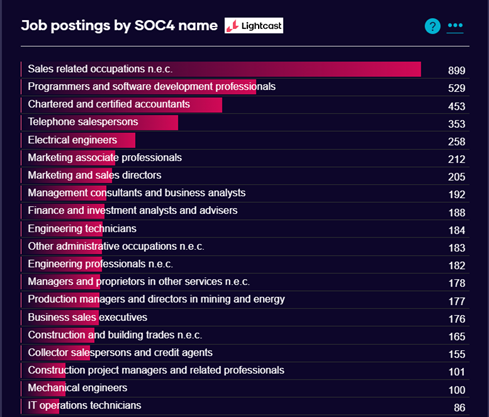

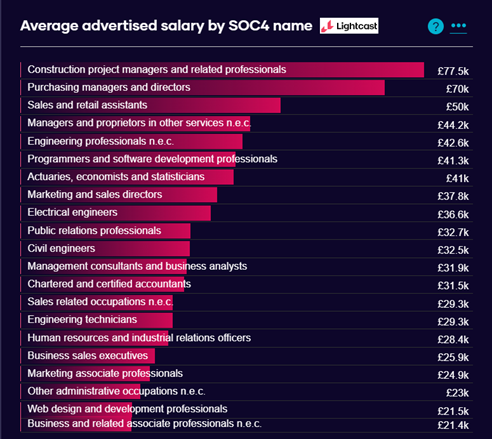

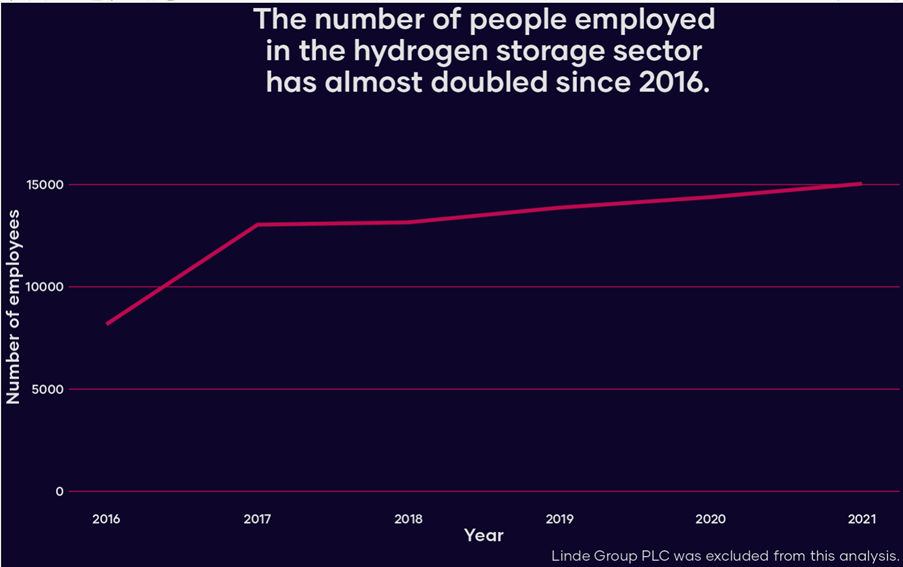

Employment has also increased significantly, with the number of employees almost doubling in the 5 years between 2016 and 2021. From the charts below, we can see that employment in this sector is in sales, electrical engineering, accountants and programmers. All these occupations are classed as higher professional occupations, and these are typically higher paid (following the NS-SEC classification).

What’s interesting is that Siemens is responsible for around 10% of the increase in employee count. In the hydrogen storage sector, Siemens is the biggest hirer of the last few years. Across their 6 locations in the UK, their employee count has increased by over a thousand people in the 5 years between 2016 and 2021, more than tripling.

What’s next?

In summary, the UK has made significant progress in decarbonising its electricity. The UK is on track to meet its ambition for offshore wind, although is that enough? Our investments in offshore wind haven’t been able to isolate us from the rise in energy prices over the last couple of years. To be able to make better use of our renewable energy and to keep energy costs lower, infrastructure investment is needed.

Using our data we can see the UK has a promising hydrogen storage sector, which is rapidly growing. We’re able to see that this growth is being driven by a handful of companies. Only time will tell if this growth spills out and we see the development of stronger clusters across the UK. We’ll certainly be keeping an eye out.

Interested in more? You can access some of the data used in this analysis on our website, as well as access a free automated reports of the sectors. Or build a classification of offshore wind on our platform and then analyse, filter, compare or export as you need to.

Disclaimer

Linde Group PLC was excluded from this analysis. Our data includes multinationals headquartered in the UK, who may have operations or derive income elsewhere. In the case of multinationals, there is no breakdown of employees or turnover by country, and we assign global employees and turnover to the UK. This is neither good nor bad, but a decision has to be made at the point of analysis whether to include or exclude companies from the analysis.

Linde Group PLC was excluded from the analysis because hydrogen storage and production didn’t seem to be a significant part of their UK based operations. Other multinationals were included because hydrogen storage was a bigger part of their core business in the UK. These checks were performed by doing quick but manual research of the companies.

Another reason for excluding Linde Group PLC was the variability of the data. Linde Group PLC was incorporated in the UK in 2018 and its employee count was around 80,000. This causes the sector to grow in size by around a factor of three in one year. Given that Linde Group’s UK presence is more limited, this increase requires some consideration and for the analysis it was seen best to remove Linde Group.