Just how helpful is it for an Industrial Strategy to pick out specific sectors? They all do it, and the current UK one is no different, identifying 8 high growth potential (IS-8) sectors to focus on. While talking about cutting-edge activities like Life Sciences sounds good in speeches, is it really that helpful?

Making policy choices between broad sectors is helpful

To the degree that any choice focuses in on the part of the economy that matters for productivity growth – something any good Industrial Strategy is ultimately trying to boost – then yes, it is helpful.

To see this, let’s split the economy into two buckets. There’s the local services part of it – businesses such as cafés, shops and hairdressers – that sell to a local market. And there’s the exporting part, made up of businesses that sell beyond their local market to regional, national or international customers. Think AI, Advanced Manufacturing and Pharma.

Local services businesses are very important for many things. They employ a lot of people. They provide important day-to-day services. And they bring amenity and vibrancy to a place. But they tend to be both low productivity and have low productivity growth potential. The job of flipping burgers, waiting tables or pulling pints doesn’t look all that different to what it did five decades ago.

Export businesses on the other hand tend to be both higher productivity and have experienced substantial productivity growth in recent decades. A job in a car factory looks very different now to what it did 50 years ago because of the innovations that have occurred in and have been absorbed by the industry over that time.

And it is the cutting-edge of these exporting activities that are responsible for creating new innovations.

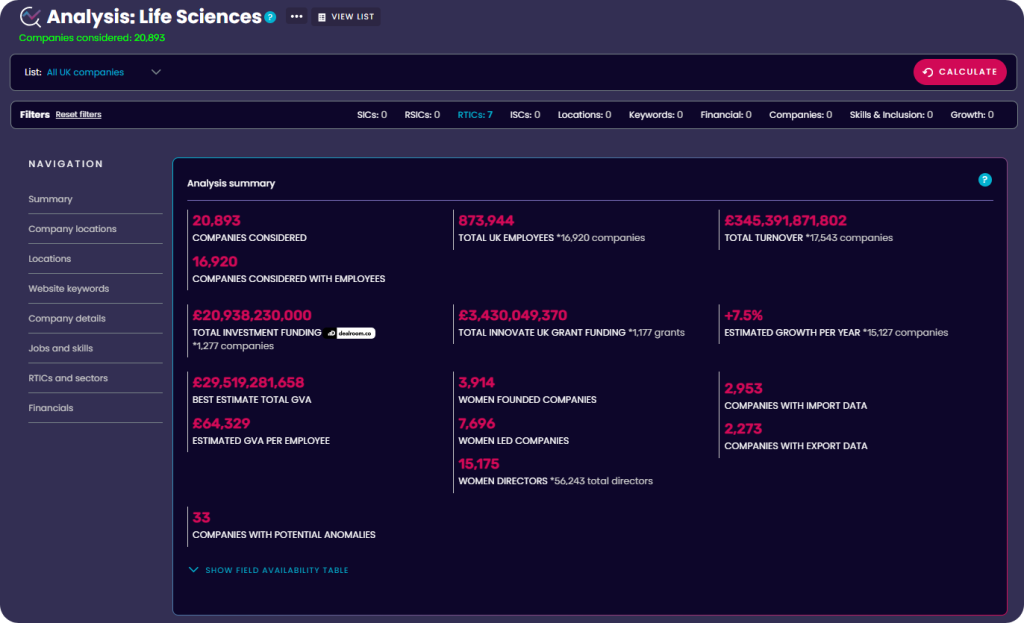

AI, Life Sciences and Wearables for example, the type of activities The Data City captures with our Real-Time Industrial Classifications (RTICs), are at the technology frontier. It is likely that it is these types of activity that will push UK productivity up in the future and so focusing policy in on these sectors over lower productivity ones, as the Industrial Strategy intends to do, is sensible.

But policy should avoid being overly prescriptive

Traditionally policymakers have treated sectors as being distinct things. This made sense in the economy of the early part of the 20th century, the time when statisticians began to formalise sector definitions. Sail makers made sails and boat builders-built boats. But it makes less sense in today’s economy, where sector boundaries are much more blurred.

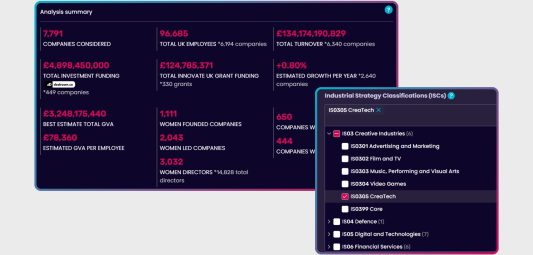

The Data City captures this blurring by looking at the range of things that companies do, rather than forcing them into one bucket or another. Illustrating how this blurring affects the IS-8, 40 per cent of all companies that have operations in one IS-8 sector have activities in at least one other.

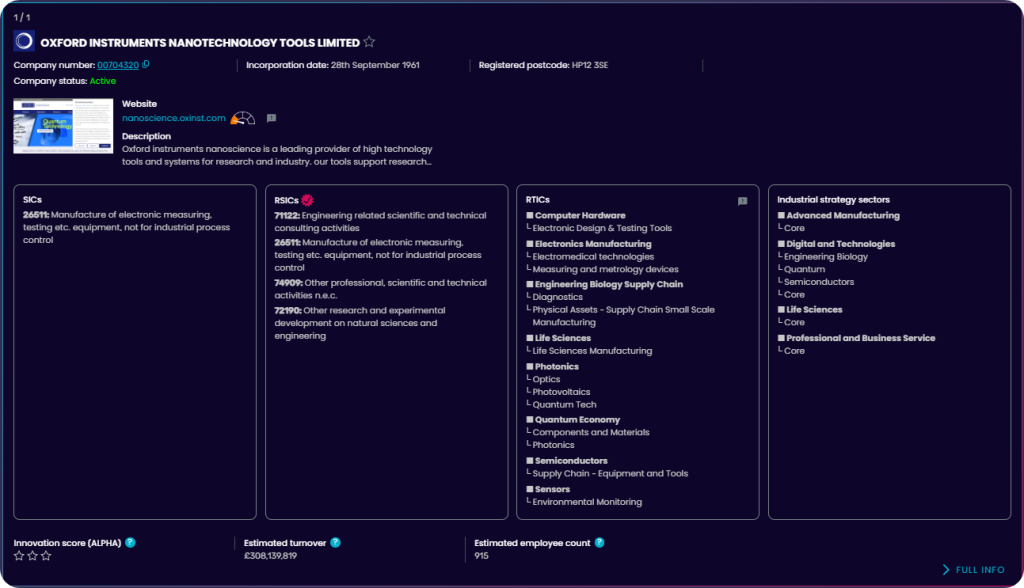

The current government has continued this black and white view of the economy, evidenced in particular by its creation of sector plans for each of the IS-8. The challenge for such a specific approach is become obvious when looking at a company such as Oxford Instruments.

It operates across four of the eight sectors: Advanced Manufacturing, Life Sciences, Digital and Technologies and Professional and Business Services. What does a sector plan mean to a company like this?

This isn’t to say that there aren’t specific things policy might do to help Life Sciences, say. But creating an arbitrary hard boundary between activities via separate sector plans feels at the very least that it is ignoring the crossover between different activities. And this crossover is not insignificant.

The ultimate goal of policy should be to support the cutting edge of the economy

A further challenge to the overly-prescriptive approach is that it becomes so rigid as to not be able to capture the evolution of the economy. It would be no surprise if at least some of the activities that will be important to UK productivity growth in 5 or 10 years’ time don’t yet actually exist. It’s pretty hard to write a plan for something that doesn’t exist.

Policy that instead aims to support the frontier of the economy will likely benefit today’s cutting edge as well as tomorrow’s. Understanding the sectoral composition of this growth will still be important, not least when it comes to measuring the performance of each component to other countries. But such an approach uses sectoral definitions to measure performance (an outcome), rather than using them to define Industrial Strategy (an input).

What does this mean for the Industrial Strategy?

This has implications for how we measure the impact of the Industrial Strategy. For example, should the sectoral definition be fixed, or evolve as the economy evolves? And should it be broad, containing any firm connected with an IS-8 activity, or should it laser in on the frontier? These are questions that we’ll be discussing at our inaugural Industrial Strategy Working Group meeting that The Data City is hosting this month with participants from public and private sector backgrounds, and we’ll report back on the conclusions from the discussion.

What to find out more about our mapping of the Industrial Strategy IS-8 sectors? Download our Open Sourcing the Industrial Strategy report.

For everything else, make sure you sign up for a free trial of our real-time platform and can see our company and IS-8 data in action for yourself.