The UK had the honour of hosting the OECD’s Global Forum on Productivity this week. This year it was dominated by discussion of industrial strategy and policy. Here are the key takeaways.

Industrial policy is back in fashion

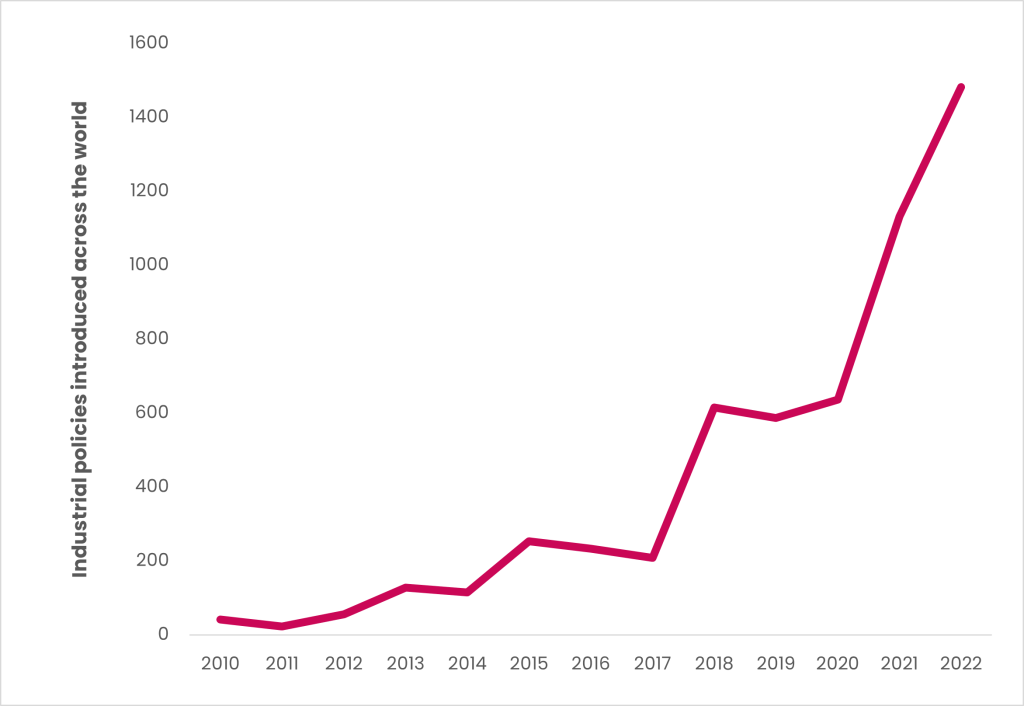

A message that came out loud and clear was that industrial policy is back. For example, Figure 1 shows how the number of industrial policies introduced across the world has increased sharply in recent years.

Figure 1: Industrial policies are becoming increasingly popular across the world

And it’s not just the UK that has launched a new industrial strategy recently. Countries such as Australia, Brazil and Finland have got in on the act too.

We need better data to chart its impact

A second clear message was the need for better data, to both better understand the economy today and to better evaluate the impact of policy intervention. The problem of Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes in particular came up a number of times.

The good news for the UK is that The Data City has created definitions for all the IS-8 sectors in the UK’s Industrial Strategy. So we can measure the IS-8 sectors today, and monitor them tomorrow.

The good news for a number of other countries is that we soon hope to be able to do the same for their economies too.

But there’s a lack of clarity about what industrial strategies and policies are attempting to achieve

One area of apparent confusion was around the purpose of any industrial strategy.

Most agreed that it is to boost growth. But what type of growth? Employment growth and productivity growth aren’t necessarily the same thing.

Is it to boost the performance of the national economy, or should it be encouraging growth in struggling areas? These things aren’t necessarily aligned.

And if it should aim to change the sectoral mix of the economy (on which there was broad agreement), how do you pick these sectors?

Should strategy back today’s strengths or bet on the future?

Let’s pick up that last tension. A number of speakers said countries should double down on what they are already good at – their ‘revealed comparative advantage’ as us pointy-headed economists would call it.

Here’s my contention with that. The role of an industrial strategy shouldn’t be to support a sector strength today. It should be to support growth of sectors that the country hopes to have an advantage in a decade to two decades from now.

There are two main reasons for this. The first is that if a country is struggling – and the UK economy certainly hasn’t set the world on fire over the last 17 years – the issue might not be what sectors it already has got, but what it hasn’t (or at least not enough of). The second is that some of tomorrow’s growth industries might not even exist yet. So giving them direct support is impossible.

There is no crystal ball to select these industries. But The Data City’s platform and Real-Time Industrial Classifications (RTICs) show these green shoots when they start to emerge, giving policy makers better information to inform their approach. A good example of this is the very recent emergence of the CreaTech sector. We’ll have more to say on this industry very soon.

While industrial policy isn’t new, the rise of big data means that we can now turn pledges on sector growth into hard numbers. If this wave of industrial policies are to be more successful than previous ones, they at very least should be driven by the data we now have available.

Want clarity on the industrial strategy and emerging sectors driving growth? Sign up for a free trial to see our data in action.